Tor understand the impact artificial intelligence can have on the economy, consider the tractor. Historians disagree on who invented the humble machine. Some say it was Richard Trevithick, a British engineer, in 1812. Others argue that John Froelich, working in South Dakota in the early 1890s, has a better claim. Still others point out that few people used the word tractor until the early 20th century. Everyone agrees, however, that the tractor took a long time to leave its mark. In 1920, only 4% of American farms had one. Even in the 1950s, fewer than half had tractors.

Speculations on the consequences of to thefor work, productivity and quality of life is at the highest level. The technology is impressive. It’s still to theThe company’s economic impact will be mitigated unless millions of companies beyond Silicon Valley adopt it. That would mean more than just using the weird chatbot. Instead, it would involve the massive reorganization of businesses and their internal data. The diffusion of technological improvements, argues Nancy Stokey of the University of Chicago, is undoubtedly as crucial as innovation for long-term growth.

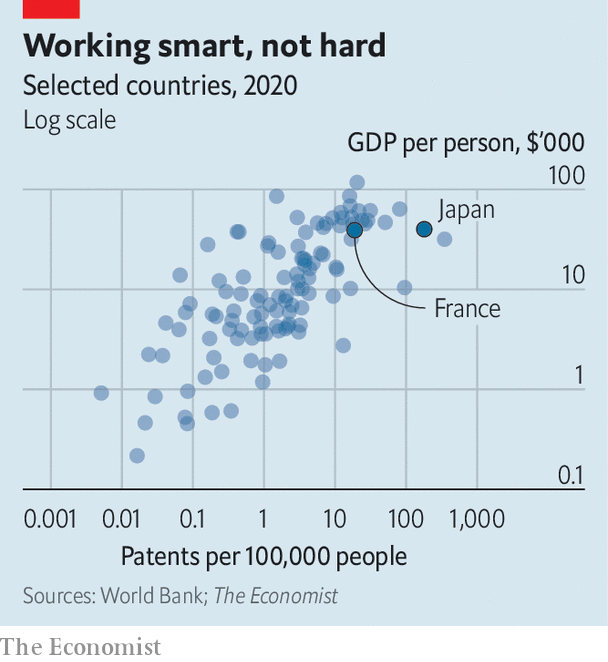

The importance of diffusion is illustrated by Japan and France. Japan is unusually innovative, producing on a per capita basis more patents per year than any other country except South Korea. Japanese researchers can take credit for inventing the qr code, the lithium ion battery and 3d press. But the country does a poor job of spreading new technologies in its economy. Tokyo is much more productive than the rest of the country. Cash still dominates. At the end of the 2010s, only 47% of large companies used computers to manage supply chains, compared to 95% in New Zealand. According to our analysis, Japan is about 40% poorer than one would expect based on its innovation.

France is the opposite. While its innovation record is average, it excels at spreading knowledge across the economy. In the 18th century French spies stole engineering secrets from the British navy. In the early 20th century, Louis Renault visited Henry Ford in America, learning the secrets of the automotive industry. More recently, ex to the Meta and Google experts founded Mistral to the in Paris. France also tends to do a good job of spreading new technology from the capital to its periphery. Today, the productivity gap in France between a top and a medium firm is less than half that of Britain.

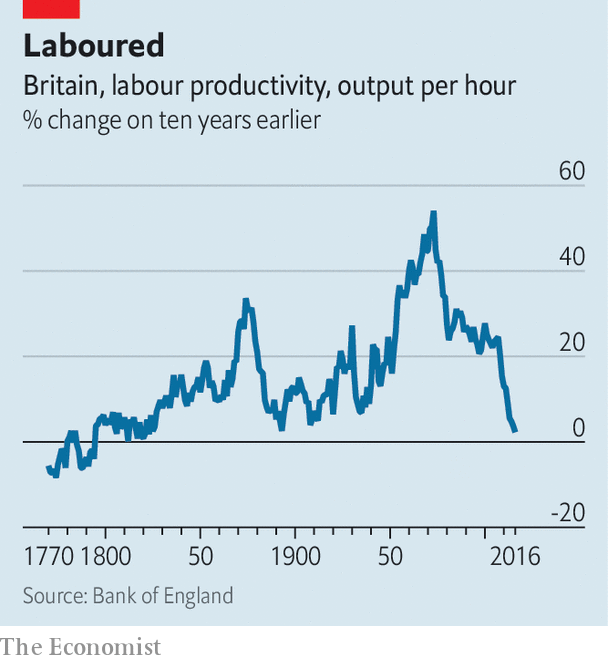

During the 19th and 20th centuries businesses around the world became more French as new technologies spread ever more rapidly. Diego Comin and Mart Mestieri, two economists, find evidence that differences between countries in adoption delays have narrowed over the past 200 years. Electricity has crossed the economy faster than tractors. It only took a couple of decades for the personal computer in the office to cross the 50% adoption mark. The Internet has spread even faster. Overall, the diffusion of technology helped stimulate productivity growth during the 20th century.

Since the mid-2000s, however, the world has become Japanese. It’s true, consumers are adopting technology faster than ever before. According to one estimate TikTok, a social media app, went from zero to 100 million users in one year. Chatgpt itself was the fastest growing web app in history until Threads, a Twitter rival, launched this month. But companies are increasingly cautious. Over the past two decades, mind-blowing innovations of all kinds have come onto the market. Yet according to the latest official estimates, only 1.6% of American companies used machine learning in 2020. In the manufacturing sector of the Americas, only 6.7% of companies use 3d press. Only 25% of business workflows are in the cloud, a number that hasn’t changed in half a decade.

Horror stories abound. As of 2017, a third of Japan’s regional banks were still using cobol, a programming language invented a decade before man landed on the moon. Last year Britain imported more than 20 million ($24 million) of floppy disks, MiniDiscs and cassette tapes. A fifth of companies in the rich world don’t even have a website. Governments are often the worst culprits by insisting on paper forms, for example. We estimate that bureaucracies around the world spend $6 billion a year on paper and printing, about as much in real terms as they did in the mid-1990s.

The best and the rest

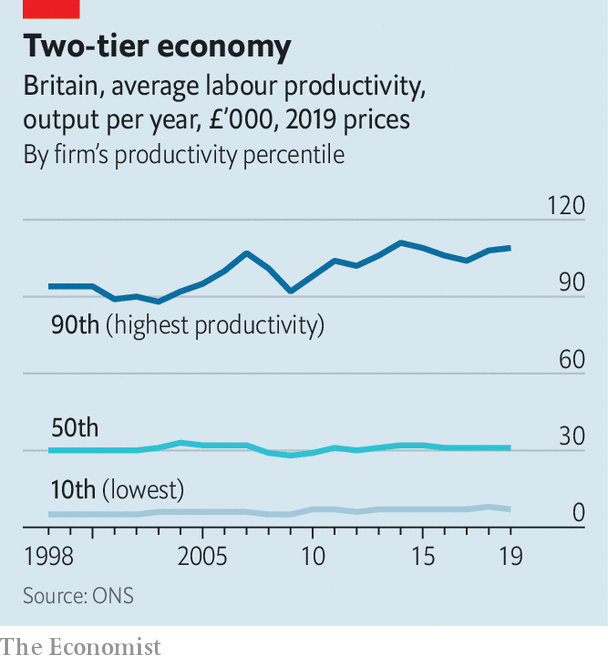

The result is a two-tier economy. Companies that embrace technology are moving away from the competition. In 2010 the average worker in Britain’s most productive firms produced goods and services worth 98,000 (in today’s money), which had risen to 108,500 by 2019. Those in the worst performing firms saw no increase. In Canada in the 1990s the productivity growth of frontier firms was about 40% higher than that of non-frontier firms. From 2000 to 2015 it was three times higher. A book by Tim Koller of McKinsey, a consulting firm, and colleagues finds that, after ranking companies based on their return on invested capital, the 75th percentile returned 20 percentage points higher than the median in 2017 , double the gap in 2000. Some companies see huge gains from buying new technology; many see none at all.

While the economy may seem abstract, the real-world consequences are eerily familiar. People stuck using old technologies are suffering, along with their salaries. In Britain, the average wages of the bottom 10% of firms have fallen slightly since 1990, even as the average wages of the top firms have risen sharply. According to Jan De Loecker of ku Leuven and colleagues, most of the growth in inequality among workers is due to widening average wage differences between firms. What, then, went wrong?

Three possibilities explain the lesser uptake: the nature of the new technology, slow competition, and increasing regulation. Robert Gordon of Northwestern University has argued that great inventions of the 19th and 20th centuries have had a much greater impact on productivity than more recent ones. The problem is that as technological advancement becomes more incremental, uptake slows as well, as companies have fewer incentives and face less competitive pressure to upgrade. Electricity provided light and energy to power the machines. Cloud computing, by contrast, is only needed for the most intensive operations. Newer innovations, such as machine learning, can be more complicated to use, requiring more skilled workers and better management.

Business dynamism fell across the wealthy world in the first decades of the 21st century. Aging populations. Fewer new businesses have been created. Workers moved companies less frequently. All of this has reduced diffusion, as workers spread technology and business practices as they move through the economy.

In government-run or heavily government-run industries, technological change occurs slowly. As Jeffrey Ding of George Washington University notes, in the centrally planned Soviet Union, innovation was the world of Sputnik, but diffusion was nonexistent. The absence of competitive pressure has dampened the incentives to improve. Politicians often have public policy goals, such as maximizing employment, that are inconsistent with efficiency. Heavily regulated industries make up a large chunk of Western economies today: these sectors, including construction, education, health care and utilities, account for a quarter of US output GDP.

I could to the break the mold, spreading through the economy faster than other recent technologies? Perhaps. For almost any business, it’s easy to imagine a use case. No more administration! A tool to file my taxes! Covid-19 may also have injected a dose of dynamism into Western economies. New businesses are being set up at the fastest pace in a decade and workers are swapping jobs more often. Tyler Cowen of George Mason University adds that weaker companies may have a particular incentive to adopt to thebecause they have more to gain.

to the it can also be integrated into existing tools. Many programmers maybe most already use it to the on a daily basis thanks to its integration into everyday coding tools via Githubs CoPilot. Word processors, including Microsoft Word and Google Docs, will soon be launching dozens of them to the characteristics.

Not a dinner

On the other hand, the greatest benefits from new forms of to the it will come when companies completely reorganize themselves around the new technology; adapting to the models for internal data, for example. This will take time, money and most importantly, a competitive drive. Collecting data is hard work and running the best models is terrifyingly expensive – a single complex query on the latest version of Chatgpt it can cost $1-2. Run 20 in an hour and you’ve exceeded the American average hourly wage.

These costs will decrease, but it may take years for the technology to become cheap enough for mass deployment. Bosses, concerned about privacy and security, say so regularly The Economist who are unwilling to send their data to edit models who live elsewhere. Small business surveys are not encouraging. One, from GoDaddy, a web hosting company, suggests that about 40% of Americans aren’t interested in it to the tools. The technology is undoubtedly revolutionary. But are companies ready for a revolution?

#employer #unprepared

Image Source : www.economist.com