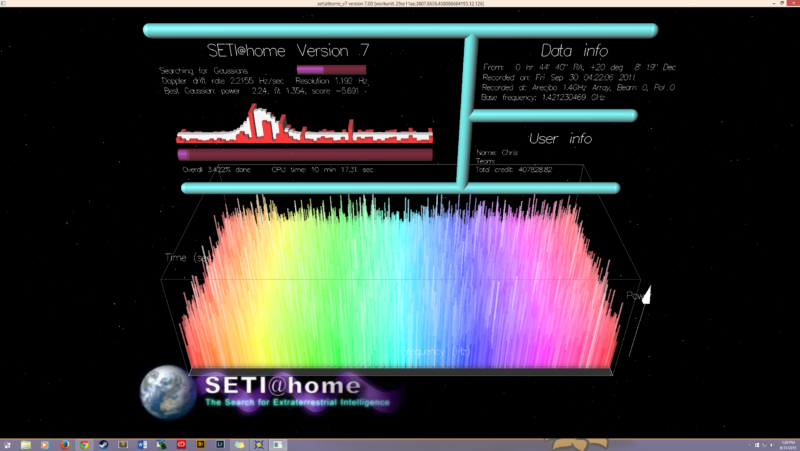

Distributed computing exploded onto the scene in 1999 with the release of SETI@home, an ingenious program and screensaver (when people were still using them) that scoured radio telescope signals for signs of alien life.

The concept of distributed computing is quite simple: you take a very large project, cut it into pieces and send the individual pieces to PCs for processing. There is no connection or communication between PCs; it’s all done through a central server. Each piece of the project is independent from the others; a distributed computing project would not work if a process needed the results of a previous process to continue. SETI@home was a prime candidate for distributed computing: each individual work unit was a unique moment in time and space as seen by a radio telescope.

Twenty-one years later, SETI@home shut down, having found nothing. An incalculable amount of PC cycles and electricity wasted for nothing. We have no way of knowing all the reasons people quit (feel free to tell us in the comment section), but having nothing to show for it is a good reason.

It goes up and down

The history of SETI@home is emblematic of the abandonment that characterizes the world of distributed computing. Another major effort came from IBM; its Corporate Social Responsibility division has been involved in the creation of the World Community Grid, a series of life science projects seeking cures for AIDS, cancer and Alzheimer’s. IBM donated its technology and talent to the project, which started in 2004. But in 2021, IBM transferred World Community Grid resources to the Krembil Research Institute, part of the University Health Network (UHN) in Toronto. A UHN spokesperson declined to comment on this story.

With the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, there has been a new treasure in the distributed world: Folding@home, a simulator that seeks to understand how proteins adopt functional structures. Folding@home has been around for more than 20 years simulating the folding of proteins to understand how diseases form. And he had something to show for this work: more than 230 peer-reviewed articles on his findings over the decades. But, with SARS-CoV-2 proteins to study, Folding@home became the IT project. So many people ran it on their computers that it broke the exaFLOP barrier long before supercomputers did.

But as the pandemic has waned, interest in the project has also waned. Greg Bowman, director of Folding@home and professor of biochemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, said the project skyrocketed from 10,000 active users to 1 million, but quickly fell to about 45,000 active users, which is still quite a gain from pre-pandemic numbers. .

Bowman thinks there’s a combination of reasons for the decline in interest. The pandemic has given tremendous motivation and plenty of time for new hobbies. Many organizations had idle computers that redirected to Folding@home. One example: FIFA didn’t need to scan YouTube for pirated content since no matches were taking place. It didn’t last, though. Inflation and energy prices have soared, Bowman said.

DistributedComputing.info, an aggregator of distributed projects, also went a few years without an update before its January 2023 update. But the site’s operator, Kirk Pearson, says he hasn’t abandoned the project; he’s just been busy with real-life matters.

Direct involvement

Pearson suggested that the focus has shifted to projects that involve users more directly, primarily at a site called Zooniverse. I agree that fewer new large-scale distributed computing projects have started in recent years, but look at all the new projects that have started at Zooniverse in recent years to see how much innovation and creativity is happening in the distributed computing world and in projects human-powered vehicles deployed, he said.

Pearson said Zooniverse is for “human distributed” projects, where humans do work for the project that computers can’t, such as identifying the numbers and types of animals in a photograph. Since Zooniverse has a relatively simple framework, it’s easy and cheap for someone to create a new Zooniverse project. This has led to the current proliferation and range of projects within Zooniverse.

It is possible that volunteers transfer to Zooniverse projects because they want more involvement in the projects, but I don’t think there is enough evidence to support that claim. I think volunteers are attracted to new projects. He suspected that if trends in participation levels in Zooniverse projects could be followed, one would see that the majority of volunteers switch from existing projects to new projects due to the newness of the new projects.

Other people attributed the decline to additional factors. David Anderson is a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, former SETI@home project director and current BOINC distributed computing project director. He wrote a lengthy treatise on the subject in early 2022. He said that distributed computing peaked in 2007 and has been in decline ever since for a variety of reasons, from a lack of mass appeal to a lack of volunteers and a strong leader with no social presence. He declined to comment further.

Practical issues

Rising energy costs are another major contributor to the decline of distributed computing. Altruism will only get you so far when your well-meaning hobby is causing your electric bill to go up. Electricity bills are generally on the rise, and the new generation of desktop CPUs and GPUs are incredibly power hungry. To make matters worse, fewer people have this hardware due to the general shift from desktop computers to laptops. Running a CPU at maximum utilization will drain even the most efficient batteries. Things have declined sharply as people are being hit by energy prices and inflation, Bowman said. I think there is a lot of interest, but energy prices and other economic factors have hurt participation.

Then there’s the fact that they have nothing to show for it. Many SETI@home users probably thought they had consumed all that electricity for nothing. In other cases, project scientific research and individual findings didn’t really stand out, they ended up in a collective pot of findings that could be discussed as part of a research paper. And the users themselves may not even know about it.

Then there’s the lack of a strong, charismatic leader, as Anderson mentioned. How do you get people excited and excited about leaving a computer running to eventually find a scientific nugget? It’s a tough sell, and in the absence of a charismatic leader, no one sells it.

Finally, projects are often boring. What initially got people excited about running Folding@home was the potential to find a cure for COVID. With SETI@home, there was the possibility of finding signals from another world. But how sexy is something like Einstein@home, looking for neutron stars? Changing the world is an easier sell.

While it may have passed its prime, however, distributed computing hasn’t completely disappeared and still attracts enough computing power to be useful. Pearson said that while some of the best-known distributed computing projects are finished, most of the less publicized projects he covers are still going strong. Distributed computing isn’t dying any more than chemistry or math is dying, he said.

Andy Patrizio is a freelance technology journalist based in Orange County, California (not entirely by choice). He prefers to build PCs rather than buy them, he has played too many hours angry Birds on his iPhone and collects old coins when he has some to spare.

#distributed #computing #dying #fading #background #Ars #Technique

Image Source : arstechnica.com