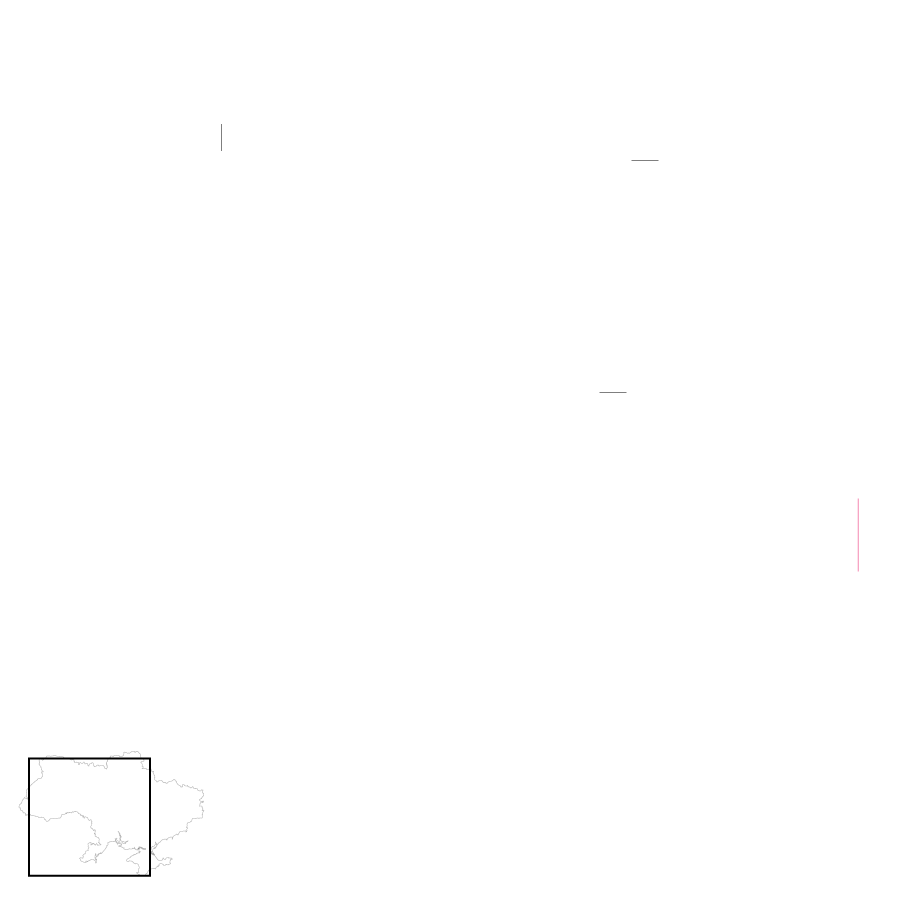

Internet traffic in Kherson is routed through Russia

Internet routing data for a service provider in Kherson shows that traffic began flowing through Russian networks in May before switching completely in early June.

Internet traffic routed through:

Source: Kentik

Several weeks after taking control of the southern Ukrainian port city of Kherson, Russian soldiers arrived at the offices of local Internet service providers and ordered them to relinquish control of their networks.

They came up to them and held guns to their temples and simply said, “Do it,” said Maxim Smelyanets, owner of an Internet provider operating in the area and based in Kiev. They did it step by step for each company.

Russian authorities then rerouted mobile data and internet from Kherson through Russian networks, government and industry officials said. They blocked access to Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, as well as Ukrainian news sites and other independent sources of information. They then shut down Ukraine’s cellular networks, forcing Kherson residents to use Russian mobile service providers instead.

internet service

supplier

Internet

service

supplier

May 29th Kherson has remained connected to the global internet even after Russian forces took control in March.

internet service

supplier

Internet

service

supplier

1st of June Then the connection closed. Russian authorities have rerouted Kherson’s Internet traffic through a state-controlled network in Crimea.

internet service

supplier

Internet

service

supplier

June 5th Russia has only added to the network infrastructure, routing more traffic through Moscow to strengthen its grip on Kherson’s internet.

Source: Kentik (traffic data); Institute for the Study of War with American Enterprise Institutes Critical Threats Project (occupied territory)

Note: ISP and traffic path locations are approximate. The service area of a provider whose traffic was routed through Crimea has not been verified and is not shown.

What happened in Kherson is happening in other parts of Russian-occupied Ukraine. After more than five months of war, Russia controls large sections of eastern and southern Ukraine. The bombings razed towns and villages to the ground; civilians were arrested, tortured and killed; and supplies of food and medicine are running out, according to witnesses interviewed by the New York Times and human rights groups. Ukrainians in those regions have access only to Russian state television and radio.

To cap off that control, Russia has also begun occupying parts of those areas in cyberspace. This separated the Ukrainians of Russian-occupied Kherson, Melitopol and Mariupol from the rest of the country, limiting access to war news and communication with loved ones. In some territories, the Internet and cellular networks have been completely shut down.

Restricting internet access is part of a Russian authoritarian playbook that is likely to be replicated further if they take more Ukrainian territory. Digital tactics have put those parts of Ukraine in the grip of a vast apparatus of digital censorship and surveillance, with Russia able to track web traffic and digital communications, spread propaganda and manage the news reaching the people.

The first thing an occupier does when arriving on Ukrainian territory is cut off the networks, said Stas Prybytko, who leads mobile broadband development in Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation. The goal is to restrict people’s access to the Internet and prevent them from communicating with their families in other cities and prevent them from receiving truthful information.

Russian redirection and censorship of the Ukrainian Internet has little historical precedent elsewhere in the world. Even after Beijing took more control of Hong Kong starting in 2019, the city’s internet hasn’t been subjected to the same kind of censorship controls as mainland China. And while Russia’s tactics can be circumvented, people using virtual private networks, or VPNs, which hide a user’s location and identity to bypass internet blocks, could be applied to future occupations.

In Russia-controlled Ukraine, internet restrictions began with key infrastructure built years ago. In 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea, the strategic peninsula in southern Ukraine, a state-owned telecommunications company built an undersea cable and other infrastructure across the Kerch Strait to reroute Internet traffic from Crimea to Russia.

Data from Ukrainian networks is now being routed south through Crimea and over those cables, the researchers said. On May 30, the traffic of Kherson-based Internet networks such as Skynet and Status Telecom suddenly went dark. Over the next few days, people’s Internet connections were restored, but they were running through a Russian state-controlled telecommunications company in Crimea, Miranda Media, according to Doug Madory, director of Internet analytics at Kentik, a company that measures the performance of Internet networks.

Russian forces are also destroying the infrastructure that connected the internet in the occupied areas to the rest of Ukraine and to the global web, said Mykhailo Kononykhin, head of information technology and systems administrator for a provider that had about 10,000 customers in the Melitopol area. He added that Russian forces were also stealing equipment from Ukrainian Internet service providers to strengthen connections with Crimea, including laying more fiber-optic cables.

A destroyed shopping center in Kherson, Ukraine where residents are forced to use Russian cellular networks.

Agence France-Presse Getty Images

In some Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine, digital censorship is even worse than inside Russia, government and industry officials say. In Kherson and Donetsk regions, Google, YouTube and the Viber messaging app have been blocked, internet operators said.

We are seeing an occupation of the Ukrainian internet, said Alp Toker, director of NetBlocks, a London-based internet monitoring service.

Konstantin Ryzhenko, a Ukrainian journalist in Kherson, said many Ukrainian websites and online banking services were down, as were social media services like Facebook and Instagram. VPNs have become essential for people to communicate and stay connected, he said.

Russia requires Ukrainians to show a passport to buy a SIM card with a Russian phone number, Ryzhenko said. This makes it easier for Russian troops to keep tabs on people with their mobile devices, including location and internet browsing.

You’re buying the device that intercepts your traffic, knows who you are, and accurately identifies all your Internet actions, he said.

In some occupied areas, internet and mobile phone networks have been disrupted, creating a digital blackout. Some Ukrainian Internet service providers have sabotaged their own networks rather than hand them over to the Russians, according to the Ukrainian government.

Anton Koval, who lived for 21 days in a village outside Kiev that was occupied in February and March, said Russian soldiers ran through the city shooting and destroying cell towers. Cut off from information and communication with the outside world, some residents have become so desperate that they have clambered to rooftops and hilltops in search of contacts.

But the Russians hunted people who tried to climb high, Mr. Koval said in an interview. When a neighbor tried to climb a tree, he was shot in the leg.

Beyond the Ukrainian-occupied territories, the Internet was a key battlefield in the war. While Russia has enforced a strict censorship regime at home, Ukraine has effectively used social media to garner global support and share information about civilian deaths and other atrocities. Mobile apps warn Ukrainians of rocket attacks and provide updates on the war.

According to the government, around 15 percent of Ukraine’s internet infrastructure across the country had been damaged or destroyed as of June. At least 11 percent of all cellular base stations, which are equipment that connect phones to mobile networks, are down due to damage or power outages.

By June, the war had destroyed or damaged about 15% of Ukraine’s internet infrastructure, including cables repaired in Irpin, near Kiev.

Ivor Prickett for the New York Times

However, in many parts of Ukraine, internet and mobile service have remained strong. Ukraine’s tech sector has been one of the few bright spots in an otherwise decimated economy. Telegram, the messaging and communication platform, remained available, even in many occupied areas.

More than 12,000 Starlink internet terminals made by SpaceX, the private rocket company controlled by Elon Musk, have integrated the coverage, said Andrii Nabok, an official at the Ministry of Digital Transformation, which is trying to restore internet access in the country. A government loan program is being developed to expedite repairs.

As Ukrainian forces have retaken control of the occupied territories, restoring internet and cellular service has been among the first tasks. On the front lines, telecommunications technicians are escorted by soldiers, sometimes facing artillery fire. Mr. Prybytko, who oversees some grid reconstruction efforts for the government, said telecom workers were the hidden heroes of the war.

The lack of the Internet or adequate communication tools is only a small part of the misery in occupied areas without electricity or water and food shortages. We’re not talking about the internet or giving some information to people, we’re talking about survival, said Yuliia Rudanovska, who lives in Poland but has family in Izyum, who have faced weeks of airstrikes by Russian forces.

Oleksandra Samoylova, who lives in Kharkiv in the northeast, said she had been unable to reach her grandmother in an occupied area about 85 miles away since April. The only word received about her were two messages saying she was fine from a neighbor who sent short messages after reaching a nearby village where there was a connection.

Ukrainian officials fear the disruptions could worsen as Russia has promised to push further into Ukraine. Government intelligence indicates that Russia is laying more fiber-optic cables to divert even more traffic in the future, Nabok said.

To help people in those areas connect to the global internet, the Ukrainian government is providing free access to select VPN services. Ukrainian officials are also seeking donations for routers and other equipment to put Internet service in bomb shelters, including schools.

The education process should continue, even in bomb shelters, so they need underground internet connections, Prybytko said.

#Russia #internet #Ukraine #occupied #territories

Image Source : www.nytimes.com